The power transfer of eBikes via electrical assist motors, from the crank motor to the rear wheel, is one of the biggest variants of different eBikes. It’s one of the main contributors to an eBike’s overall character. Each type of transmission has specific applications, some more versatile than others, but there is quite a lot of choice, so it’s worth understanding the pro’s and con’s of each and how it will affect the type of eBike you may be looking at purchasing.

The 2 main categories are derailleur (aka “mech”) and hub gears, but there are also combo systems of those 2, plus some other slight variants.

Derailleur systems.

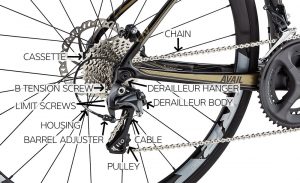

If you’re really new to derailleurs, it may be worth a little bachground reading on Wikipedia. Put as simply as I can, a derailleur uses a chain with a spring loaded, adjustable jockey wheel that moves the chain over a cassette of varying sized chainrings.

This derailleur is adjusted (ie moves the chain onto different chainrings) at the handle bar. They are indexed with audible “clicks” between gears either with a thumb/finger shifter or a twist grip. Twist shift tend to be used in conjunction with hub gears; finger/thumb shifters tend to be used with derailleurs. Both of these types can be cable (aka “mechanical”) or electronic (the most common of which is Shimano’s Di2 gear shifting system, which has hub gear and derailleur variants).

Derailleur cassettes commonly have 8, 9, 10 or 11 chainrings – but more is not necessarily better. They all have similar gear ranges that change the gear ratios of around 0-400%, but with fewer chainrings there are just less in-between gears. SRAM’s new eBike specific groupset for example has only 8 cogs on the cassette and they are not a cheap option – instead they are thicker and designed to change gear under extremely heavy torque loads. The more expensive cassettes use different materials, construction techniques, coatings and different levels of machining that include subtly shaped shifting “ramps”. Shifting ramps often look very subtle, but make a huge difference to the gear shifting performance, accuracy and speed. For example, Shimano’s top end 11 speed cassette uses hard-coated steel and titanium cogs mounted to an aluminium carrier or “spider”, where it’s clearly seen a huge amount of very intricate CNC machining.

Derailleur strengths and weaknesses

Probably the biggest strength of derailleurs is their ability to change gear during high load on the chain. It can make a few cracks and bangs during shifts, but it’s little more than noise.

Derailleurs are also reletively very lightweight and cheap to buy – mostly due to the vast numbers in which they are produced. The derailleur was invented around 100 years ago (see the Wikipedia link earlier) and it’s evolved a lot over that time. Today’s derailleurs can handle a lot of mud, crap, neglect and water, but they are still relitively sensitive to set up. They really need to be attached to a very straight piece of metal from which they hang (hence the term “hanger”). Their other main weakness is longevity. The derailleur itself can last many 100’s even 1000’s of miles, but the chain and cassette can wear very quickly – which need changing when worn as they rely on a spring loaded jockey (ie the derailleur) in order for the chain to properly mesh with the chainrings. When the chain and chainrings become worn, the chain will skip over the chainrings under high torque. A chain can become worn in as little as 100 miles if the bike is used in a lot of mud, water and in hilly areas.

Another strength of derailleurs is their efficiency as it’s purely a chain transmitted power delivery, therefore power loss is less than 1%. Its also very immediate power transfer and not rubbery.

And finally, it can be seen as a weakness of derailleurs that changing gears requires cycling the transmission (ie pedalling) so you can’t change gear while stationary or at the very last second. Personally I don’t feel this is a huge draw back as you do become used to pre-empting gear selection with practice.

Derailleur applications on eBikes

The biggest use of derailleurs on eBikes is simply when there’s a high torque motor. Shimano for example won’t allow their hub gears to be spec’ed on Bosch’s Perforamce CX motor as it produces too much torque for the hub to handle – but derailleurs are perfectly fine for this application. They also tend to be spec’ed on all eMTB’s – a lot of this is history and tradition, but also because of some of the downsides of the alternatives are pretty bad – read on….

Hub gears

The most obvious difference with hub enclosed gearboxes is that they are completely self-contained. Even the hubs don’t look particularly different, so they basically appear to be a single speed drive system.

Hub gear systems for bicycles were also first implemented around 100 years ago – see this Wikipedia link.

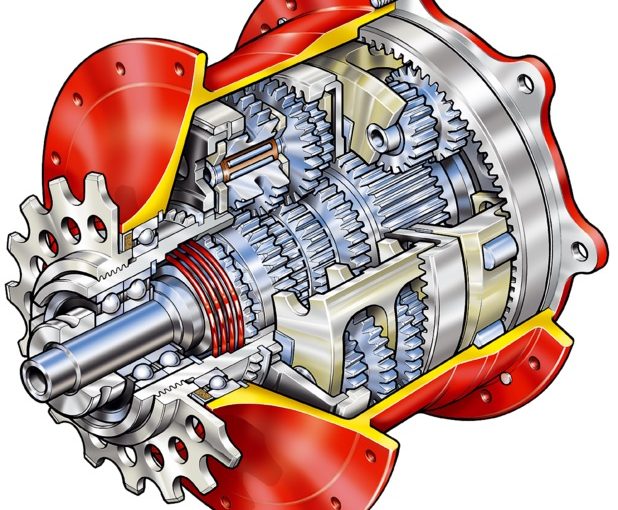

In eBike applications they generally have 7, 8 or 11 different gears (14 gear hubs also exist for bicycles, but are not generally used on eBikes as factory spec, mostly due to high cost). By far the biggest manufacturer of eBike spec’ed hub gears is Shimano, ie well over 90% of all hub gears spec’ed at factory on eBikes are Shimano, which all feature planetary style gear mechanisms.

The handle bar mounted shift-mechanism options are the same as derailleurs: finger/thumb shifter, twist grip shifter or electronic button.

Hub gear strengths and weaknesses

Hub gears biggest strength is the low-maintenance aspect. The suggested service interval for a Shimano Nexus 7 or 8 speed gear hub for example, is 10,000 miles and even that is conservative. Realistically, hub gears should run pretty much un-serviced for the lifetime of the eBike. Because the system is completely self-contained, it is isolated from all weather conditions, mud, grit and other contaminants.

Likewise the chain on hub gear eBikes tend to last for huge maintenance intervals, this is because the chain can be much thicker and also because its impossible for the chain to slip over the chainrings as it’s a fixed system – not one that relies on tensioning the chain via a spring loaded derailleur.

Sadly, that’s pretty much where the strengths end for hub gears; there are quite a lot of downsides….

Wheel removal – hub gears require a sliding frame drop-out in order to tension the chain. That means the axle needs to be held in place very tightly, so they use axle nuts, not a QR axle, so you need spanners to remove the rear wheel and it’s not particularly quick! It also makes them tricky to use with disc brakes – it’s not impossible, but frames must have some system of drop-out that is both horizontally adjustable (to get the chain tension) and will also place the disc brake caliper in the correct place over the disc rotor.

Rear suspension compatibility – with a suspension frame, the distance between the rear axle and the crank axle varies as the suspension moves up and down it’s travel – it is not fixed. In order for the chain to stay tensioned, a jockey wheel is required. This is where derailleurs offer a secondary use of their spring loaded jockey wheels. Adding a jockey wheel to a hub gear system is an extra faff needed to adapt them to suspension frames – which also leads me to the next downside…

Weight – Hub gears weigh quite a bit more than derailleur/cassette systems, this is especially bad on suspension frames as increasing the unsprung mass in relation to the sprung mass, decreases the suspension’s sensitivity to bumps. Don’t over-analyse that – you can read endlessly into it and just end up confused, but just remember that unsprung weight = bad. It can make a bigger difference than you might expect.

Low Torque only – as mentioned earlier, hub gears can’t take infinite torque. The cogs inside them are pretty small and the axles they turn on will eventually bend and snap. Shimano only allow 55Nm max capacity on their hub gears, so even Bosch Performance drives have to be “down-tuned” from the usual 63Nm (although max power output remains at 600 Watts)

Problems are not easily solved – despite their low maintenance, problems do occasionally happen, and when they do, it can be difficult to diagnose and fix. A mid-ride hub gear issue will almost certainly mean that the eBike ride is over – there are rarely quick “trail-side” fixes.

Loss of efficiency – not much of a big deal this, as most of the power comes from a motor/battery (ie not your legs), but whenever power is transferred by cogs (and not chain alone) there is a power loss of around 5% as a minimum.

The final downside of note is the gear shift of planetary hub gears. Gear shifts on the whole have to be done while the transmission is not in motion – ie you have to briefly stop pedalling. You can use this to your advantage, for example when coming to an unexpected or ugent stop after travelling at speed – you can change gear while completely stationary, back through the whole range, in order to set off again easily. If you try to change gear while pedalling and there is even a medium amount of strain going through the transmission, it can miss-shift or “grind” and fail to engage; it can also cause premature wear inside the hub.

Cup & cone bearings – due to the majority of hub gears being manufactured by Shimano, that also brings with it the dreaded cup& cone or “open” style of axle bearings. This has caused much debate over the years and Shimano has stuck to its guns on the matter and simply will not recognise the advantages of a removable “cartridge” style bearing. Personally, I think Shimano are plain wrong on the matter, but it doesn’t change the fact that for the foreseeable future hub gears are stuck with open bearings – which, when the cups become worn, are not replaceable. That’s fine if they never get mud inside….

Hub gears applications on eBikes

As I’ve already established, hub gears don’t really suit eMTB’s, so they’re only fitted to city hybrids and trekking eBikes with lower torque output motors. It suits eBikes where the user doesn’t want to be bothered with maintenance (that’s most urban commuters and holiday/distance trekkers), especially for high mileage users. It very much suits roads with traffic lights too, due to the ability (and necessity) to change gear while stationary. It also suits hire fleets and it’s a more robust system overall with close to zero wear and little required maintenance.

Combination hub and derailleur (SRAM 30 speed)

Just a quick note on this, as there’s only 1 combo system that I’m aware of – that being Sram’s “Dual” hub, which contains a 3 speed hub gear with a 10 speed casette, thereby creating 30 possible combinations. Realistically, it’s application to eBikes is largely pointless as it extends the useable gear range way beyond the assistance provided by a legally restricted eBike. What tends to happen with Dual drives is the cassette is used as normal, but the hub gear is left in gear 2 for 95% of the time. It’s still something customers who haven’t owned eBikes before ask for though – as they’re afraid that 8, 9 or 10 gears won’t be enough.

Well, most cars have 6 gears – do you wish they had 18 so they would more easily cruise at 150mph? No, me neither.

Nuvinci electric and mechanical

Again just a quick note on this specific brand of hub gear (as I think Nuvinci own the patent) – it’s a hub gear, but NOT a planetary gear system. Instead it runs on the variable circle diamters of the edge of a ring of sphere. Here’s a video explain it, but if you struggle to understand that, well its kind of similar to cone gears. The main advantage is the ability to change gear infinity finely AND during high torque load. It’s a great idea in principle, but has a bit of a rough history with reliability issues.

It’s also worth noting that this system is what Continental have incorporated into their new eBike motor and integrated gearbox. I wrote about them recently here.

Summary and future

So there you go – that’s the long version of eBike gear system choice!

In the future, I think all eBike components will steadily evolve away from being shared by standard bicycles and this is especially true of gear and transmission systems. There simply isn’t currently an ideal gear system made for eBikes and there really could be – and needs to be! All the current options are simply adapted bicycle parts (even if slightly beefed up), which are not designed for the long-term, high torque eBike motors already available. It’ll take time not only for parts to be developed, but also because the emergence and acceptance of eBikes is still very new and fragile. During the next chapter of eBikes, I think they will need to continue to closely resemble bicycles in order to gain acceptance and become “normal” – so parts sharing with bicycles will continue for a while yet. With time and more sales of eBikes, when they do eventually become the norm, this is when eBike specific components will start to become proper and specialised.

I think Continental’s integrated gearbox and motor that I tested and wrote about last week is a pretty big step forward. I hope to see other systems like this soon…